Art on Computers: Man, Myth, and Medium

In a new series, we explore how digital art challenges traditional creativity, raising questions about technology's role in artistic expression and how we experience art

Abigail Leali / MutualArt

Feb 12, 2025

In the last couple of decades, we’ve seen a monumental shift in the way we process media – at least, that’s what I’ve heard. I was part of the first generation to face my “formative years” with a smartphone in my hand and a keyboard at my fingers. My true introduction to art, like that of many of my peers, came from homemade tutorials on YouTube. My high school class pioneered our school’s Chromebook program; I learned biology from Google and Wikipedia, and, outside of standardized testing, I haven’t handwritten an essay since I was twelve. Sad as the truth may be, I’ve accepted that I write better on a screen than with a pen and paper – on a word processor, I can fit my words and phrases and ideas together like puzzle pieces. Not to mention, I can type much faster than I can write. Sometimes faster than I can think.

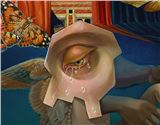

David Revoy, Artwork for the preproduction of the fourth open movie of the Blender Foundation 'Tears of Steel' (project Mango), 2012 (CC BY-SA 3.0)

These are confessions that, for a long while, I was loathe to make. My teachers, mentors, and heroes have all generally been champions of the analog: books and notebooks, deliberate penmanship and editorial markings, allowing each sensation and movement to connect you with your craft. They are right, I still believe, and my every encounter with physical media only convicts me further that only real, tangible objects can induct us into the full richness of existence. Most recently, I discovered it again when I had the great pleasure of seeing Katsushika Hokusai’s Great Wave in person. Though I had seen it copied and printed a hundred different ways, there were so many details that only an original print could capture: the interplay of the ink with the texture of the paper, the palpable “absence” of its negative space. Standing before the work of a master who, in his own right, grappled with the changing world of information technology, I was reminded, yet again, of how different my engagement with art in the “digital world” has been to that of generations past.

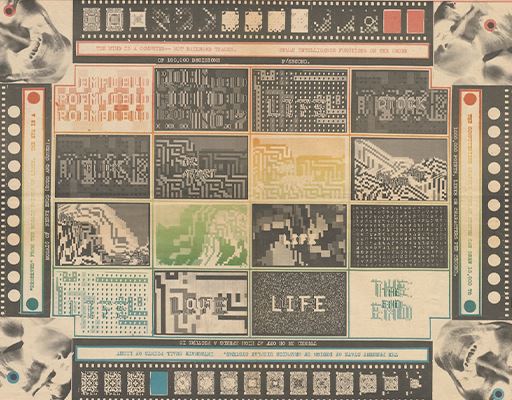

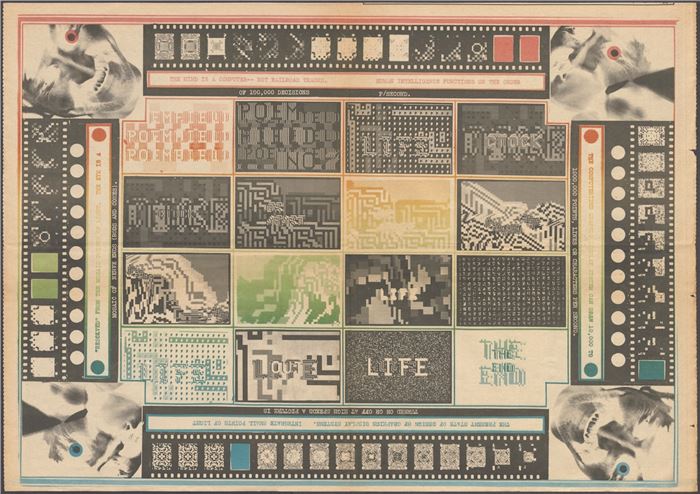

Dorpat, Paul, center spread for Helix, 1968

Dorpat, Paul, center spread for Helix, 1968

The experiential rift cuts deep between Hokusai’s original viewers and us today. And I can sense a bit of it, too, between my parents and myself. Though I suspect the increasingly overwhelming prevalence of technology in our culture may be lessening the divide between older and younger generations concerning digital media, there is a subtle difference I’ve found has lingered. For those who encountered the great privilege (and pain) of having to travel to the library for books, to the theater (or at least the living room) for movies, and to the museum for art, the Internet takes the role of information transport: a conduit enabling two real-life, substantial entities to communicate with each other amid a vast network of connections. That may be accurate, but I’m not sure it fully captures the enormity of the digital sphere.

MOMO Studio, Illustration of a person, tasting food with a spoon, standing in a home kitchen, 2025

MOMO Studio, Illustration of a person, tasting food with a spoon, standing in a home kitchen, 2025

As more of us spend more of our lives online, we are becoming more comfortable with a different conception of the digital world, one in which we are, for all intents and purposes, the only “material” element in the system. There is no concrete “recipient” to catch our words and creativity; it is only us and the parasocial void. The Internet has morphed from a means of communication into an all-encompassing forum that guides and manipulates our lives.

George Grie, Lost City of Atlantis or Mystery Legend Atlántida, 2014

George Grie, Lost City of Atlantis or Mystery Legend Atlántida, 2014

It’s almost a paradox. The algorithms that mold our digital experience can exact useful information about our “real” lives only in exact proportion to how fully we relinquish ourselves to their curated unreality. The deeper you go, the fewer tethers remain to bind you to the world technology is meant to augment. Consider: How little of the content you’ve consumed today exists beyond your screen? How much of it has any bearing on the way you will spend the next few hours, let alone the next few years? Somewhere along the way, we’ve gotten comfortable with the idea that we might just be able to contain all of life – ourselves included – in little more than ones and zeroes.

Olli Kilpi, 2025

That sounds dystopian, I grant you. But any culture brought to extremes will become dystopian, and I do not believe humankind is capable of staying at extremes for long. Still, these fears about technology’s leviathan role in our daily routines seem to extend to every area of life – and, perhaps most urgently at this stage, with regard to human creativity. Hence, people are wary of digital art. Whether they object to its generally mass-market appeal, its fantastical characters, creatures, and landscapes that too often strain one’s suspension of disbelief, or to the constant worry that it is fueling (or disguising) the steady march of progress towards our species’ obsolescence, one question seems to lie at the core of the matter: Does creating art with the aid of a computer makes the work less than human?

Maybe. Or maybe not. It depends on the artist – and on your definition of art. And also, on your definition of humanity. After all, what does it even mean to be a person? What constitutes creative activity, and is it really a distinguishing factor between man and beast, or man and machine?

David Revoy, Artwork for the preproduction of the fourth open movie of the Blender Foundation "Tears of Steel" (project Mango), 2012 (CC BY-SA 3.0)

I am grateful to announce that these are questions that far exceed my pay grade. Instead, in this new series, my more modest aim is simply to demystify digital art. What is it? How does it work? How does its market differ from that of traditional media? What threat does AI pose to it? Is it so easy a computer could do it?

Well, first off, as a traditionally trained artist who has struggled for several years now to wrap my head around even basic digital techniques, let me be the first to tell you that it is far more than “art with computers.” It is not easy. It is hard. Even with a stylus and tablet that mimic pen and paper as closely as possible, it is still hard. Even with a cogent understanding of the programs that undergird the software’s mechanics, it remains hard. Digital artists rely each day on an ever-changing, carefully constructed world brought about by centuries of advances in mathematics and science. Their mastery and intuition of the medium they’ve chosen can certainly hold up against those of any tangible medium. And despite popular misconception, they must grapple more than anyone with the ideological consequences of their work as we look toward the future of technology. How do they balance their online worlds with “reality”? What does that distinction even mean?

I look forward to exploring with you.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page