Book Review: Wagner and the Avant-Garde

An exploration of the influence Richard Wagner’s operas had on modern art lacks sentiment to properly represent the romantic composer’s impact

Michael Pearce / MutualArt

May 08, 2024

Richard Wagner and the Art of the Avant-Garde 1860 – 1910, David Rosenthal. Rowman and Littlefield

David Rosenthal’s little book about Richard Wagner’s influence on European art is an introduction to paintings, lithographs and drawings inspired by the subjects of his operas. The title is misleading, for the word ‘avant-garde,’ which would certainly have been understood by Wagner and his contemporaries as a term specific to collectivist propaganda, is misused by the author to describe all artists who “reject existing stylistic norms by seeking new modes of expression.” With this wobbly first premise, Rosenthal plunges into the headlong sea of Wagner paddling a leaky life-boat. Perhaps he might be forgiven, for the abuse of ‘avant-garde’ is commonplace among lazy art historians persuaded by the theoretical rhetoric of the propagandists serving the cause of the American art establishment, who are dependent upon the strange idea that radical novelty should be the priority of all art, and Rosenthal seems uncomfortable among them. Defining the parameters of his avant-garde, he writes, “The emphasis here is on artists who, from the viewpoint of the twenty-first century, either had highly individualistic styles, or contributed in some way to what is understood today as the history of modern art.” But his is an impossible position, full of contradiction, for it is beyond challenging to fold the swollen sails of supremely romantic Wagner into the austere harbor of the conventional avant-garde academy, when the fundamental premise of the avant-garde is its absolute contempt and opposition to kitsch – which depends upon sentiment – and sensual Wagner is stormy sentiment embodied. Rosenthal’s position would send Clement Greenberg whirling in his grave.

Rosenthal opens weakly with a gouache painting attributed to the great painter Eugène Delacroix, whose theatrical style would seem to be kissing cousin to Wagner’s operatic sturm und drang, and this should have been a promising start to the book – not least because Delacroix was a supreme romantic, and also, on occasion, a genuine avant-gardist master of the Saint-Simonian tradition, and thus he would appear to be the apotheosis of Rosenthal’s title – but the author quickly explains the picture was probably not actually created by the great master of spectacle, and was falsely signed in his name by an unknown follower. Furthermore, Delacroix “…does not seem to have painted any subjects drawn from operatic librettos.” Consequently, Rosenthal’s first foray falters with this example explained away merely as Wagner-adjacent. Sadly, an imagined Venn diagram of great Delacroix’ sublime work and the epic world of Wagner’s operas would show little overlap between them, other than that each artist had a general desire to embrace the glories of the sublime – which was common cause to many members of the bohemian class emerging with the urban onset of the industrial era.

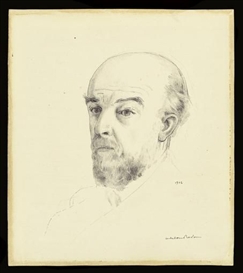

But all is not lost! The fascinating Symbolist Odilon Redon was doubtlessly inspired by Wagner’s music, especially evident in his lithographs of Brünnhilde and Parsifal, and a drawing and two pastels, and Rosenthal does sterling work evaluating the artist’s hand. Next, a surge of Pre-Raphaelite stunners sweeps to shore in a wave of feminine sensuality, and Rosenthal seeks the ideas that spill between Wagner and William Morris, Holman Hunt, and John Millais, finding overlapping interests in the plays of Shakespeare. It is even harder to imagine the Pre-Raphaelite painters, who were famous for their reactionary medievalism, as members of any avant-garde, either political or novel. Despite Holman Hunt’s honest Christian charity, and William Morris’ odd expression of his socialist affectations – contradicted by his peculiarly bourgeois admiration for the wonders and luxuries of expensive hand-made craftsmanship and the sensual pleasures of the treasures he crafted at his country house Kelmscott Manor – and although the PRB did introduce a new species of revived and Victorian romanticism to art, it was treated with utter contempt by the modernists. Their association with Wagner also seems to be limited to shared primary sources, especially Malory’s Le Morte D'Arthur, rather than directly linked by either great admiration or emulation.

Rosenthal includes Aubrey Beardsley in his Pre-Raphaelite chapter, although the chronological overlap is slender. In Beardsley’s work the direct relationship to Wagner’s operas is explicit. He was “a fanatical Wagnerite,” and produced more than twenty lovely images in ink and wash based on Tannhäuser, the council of the gods from Götterdämmerung, and Siegfried and the dragon. Wagner’s were the only operas he cared to illustrate, and Beardsley died with a photograph of Wagner set up like an altar. In this chapter, Rosenthal’s insights become truly valuable and hints of passion at last emerge from his pedestrian prose.

A chapter on the Wagner Memorial Album of 1884, includes a diverse compendium of unusual works by artists who produced images to commemorate the death of the great composer, including an obscure and uncharacteristic Fefnir as a Dragon Guarding the Nebelung Hoard by dark master Arnold Böcklin, who Wagner once approached to design sets for Parsifal. The painting is completely unlike anything else produced by the moody painter, and was an astonishing addition to the canon of Böcklin’s work, and is completely unknown except by reproduction in the Album. Max Klinger’s Ascent to the Grail Mountain was a lovely Northern landscape, with the shining city poised in the distance, set between heaven and earth. Henri Fantin-Latour was an enthusiastic Wagnerian, and produced dozens of paintings and lithographs based on the operas.

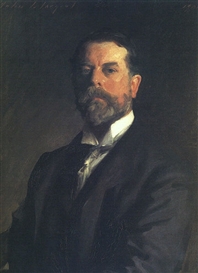

Surprisingly, young John Singer Sargent, better known for his scrumptious portraits of women of the haute bourgeoisie and aristocratic ladies, contributed an ink and wash Death of Tristan. As an avid servant of the rich, Sargent was certainly no avant-gardist, but he became an avid Wagnerite, and Rosenthal traces the development of the young American’s enthusiasm, which sadly never translated beyond sketches into paintings.

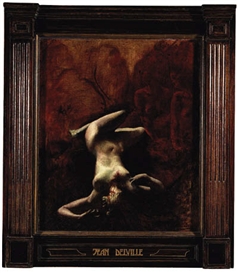

James Ensor is the closest representative of the modernist avant-garde included in the book, and his Wagnerian works are more mocking than flattering, more satirical than painterly, and already filled with the political skepticism that characterized twentieth century art after the wars. Here at last, in a chapter on Wagner’s influence on the artists of the Belgian avant-garde, Rosenthal’s title finds its proper home – but carries his narrative into the late 1930s. The chapter continues with symbolist Fernand Khnopff, whose appearance is justified by his drawings of Isolde after she has drunk the love potion, and his lost designs for Parsifal, reported in The Studio in 1912. Another Symbolist, Jean Delville, also had a deep interest in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, and his charcoal Parsifal is one of the most beautiful images described in the book. A mercifully brief chapter describes sculptor Constantin Meunier’s mediocre bronze Valkyrie.

Given his loose definition of ‘avant-garde,’ it is puzzling that Rosenthal has ignored the glorious art nouveau illustrations of Hungarian Willy Pogany, who was born in 1882, and produced wonders of pen and ink and print in his Wagnerian masterpieces, Tannhauser, 1911, Parsifal, 1912, and Lohengrin, 1913. Rosenthal willingly wandered into the 1930s with Khnopff and Ensor – why not stretch to the delights of wonderful Pogany, who adored Wagner? And if we are stretching the boundaries of avant-gardism to include the Pre-Raphaelites, then where are the fantastic Wagnerian romances painted by Ferdinand Leeke and the amazing spectacles of Max Brückner, who surely made extraordinary advances in the manifestation of the gesamtkunstwerk, the “total work of art” of Wagner’s innovation.

Contrasting heavily with the imaginative topic of his investigation, Rosenthal spends little time on developing his own ideas, cautiously grounding the structure of the book on identifying artists linked to the operas of the great composer – sometimes distantly linked – then describing their works, limiting himself to reporting the pictures as they appear, without adventuring into either allegorical or ethical interpretations, or the mystical implications of the lofty subjects of the paintings or prose which inspired Wagner and the artists. He makes little effort to rise above the most basic premise of art criticism, which is simply to assess the physical reality of the work of art in question, and he spends long passages of his prose on mediocrities – and surely a book about Wagner should be full of flair and the drama and emotion of bombast, but Rosenthal offers little in the way of interpretation or exploration of the grand themes of the art, does little to expand on his brief mentions of the great drama of the gesamtkunstwerk of Wagner’s oeuvre, and makes few allusions to the great discussion of the nature of the sublime which dominated the thought of the romantics in Wagner’s time. This is Wagner! This is the man who wrote, “Music is the inarticulate speech of the heart, which cannot be compressed into words, because it is infinite.” This is the man who composed the enormity and spectacle of Ride of the Valkyries! Where is your passion, Dr. Rosenthal, where is the speech of your heart?

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page